Luis Miguel's reflections from a training with activists and community organizers from Portugal, Netherlands, Spain, Italy, Poland, Germany and France held at La Casita de Colores.

The place is called Eroles. On the journey up, I drift in and out of a half-dreaming, half-sleeping state. The landscape transforms into shapes in which clouds, mountains and rainbows intertwine in one and the same. After weeks of rain, you can smell the moisture in the air. Rivers echo through the valley with a strength that this dry region has not seen in a long time. Waterfalls emerge from the cliffs, searching for long-forgotten paths. We ascend the mountain almost like flying as the sun slips beneath the horizon.

Upon arrival, I am presented to the house where we will be staying for the next week – “La Casita de Colores”. Here we will be learning about Conflict Transformation together with activists and community organizers from Portugal, Netherlands, Spain, Italy, Poland, Germany and France.

In my practice as an urbanist I often act as a neighbourhood facilitator or mediator. Conflict is therefore an inseparable component of my practice. I have been strongly influenced by Donna Haraway’s “Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene” but if I am completely honest I would not say that I have been able to hold spaces for conflict in the extent that I think it deserves. The rise of far-right extremism, in my view, is tied to the disintegration of our communities—symbolically and physically—and to the growing need to renegotiate how we share space, resources, and our shared existence.

I think that my conflict avoidance tendency might be connected to my instinctive search for harmony in the presence of discomfort, or perhaps also from a diplomatic, overly polite academic background that discourages direct engagement with tension. In any case, I came to the training with the strong conviction to fundamentally question my relationship with conflict, particularly with a focus on how to imagine new ways of addressing conflict in public spaces, how to make sense of the distinction between personal and group needs, and how to address conflict in the groups where I am active. I was craving for some tools and frameworks but most importantly, I was craving for a deep breath and the spaciousness that honest reflection brings into my life.

Conflict definition and levels

One of the first ideas that struck me during the training was the framing that conflict requires something to be at stake. Simple but poignant. Some aspect of a relationship between two or more interdependent actors needs to be at play and that can be the relationship itself, influence over a place, leadership or the identity of a group.

Conflicts are, however, not to be confused with misunderstandings, as I often tend to do. In my world of fantasy, things are always resolved with a conversation because I assume the best from people and there is a conflict it is for sure because the other person has not get your point completely through, or has not fully understood your needs. This lack of understanding also plays a role in conflicts, but it is fundamentally different from what miscommunication is, in the sense that conflicts require something to be negotiated implicitly or explicitly rather than just a misunderstanding in which communication has simply failed and a clarification can be enough to move forward.

This implies that the negation of a conflict does not make the conflict disappear, it just locks out the possibility of transforming it until it escalates. Conflict transformation is therefore very connected to our capacity to exchange, to express our needs, to listen to those of others and ultimately to negotiate how and to what extent we can move our positions.

Conflict crosses our lives in many dimensions. At the very personal one, at interpersonal level, at group level and socio-cultural level. One interesting frame that helped me to gain perspective on the topic was that one of not fully identifying myself with the parts involved in a conflict, even if they belonged to my experience. In the case of intra-personal conflict, this would mean understanding internal conflict as a contradiction between inner voices. In the case of inter-personal conflict it would be to look at it as a conflict between the positions that we occupy and the beliefs, needs, identities associated to it rather than just personality clashes. In the case of group conflict it means that there are roles arising within the group dynamic which come into conflict, and these roles may be carried by different people at different times. For example: the timekeeper vs. the dreamer. And finally in the case of socio-cultural conflict it represents a collision between normative systems or what is considered right, valuable, or appropriate in a given context.

Group culture and emotional literacy

The culture of a group is revealed in how it handles (or avoids) conflict. Early in the training, we were introduced to a tool that helped me to make sense of group culture and the basic components that define a group. This tool consists in a triangle with three vertices: the “how” (processes and dynamics), the “what” (objectives), and the “who” (people and relationships). All three components represent roles that belong to any group, which can be at times, if not always, in conflict. For example, a group tension in which there are people more focused on nourishing the interpersonal relationships within the group and some others on developing strategies to achieve the goals of the group. The conflict or tension in this scenario could be associated with the management of time, the prioritization of tasks or even the group’s identity. Roles can be represented by different people at different times, and it does not mean that the conflict has to do with the people embodying those roles: the conflict just highlights an aspect of a group that requires further clarification. In a sustainable group dynamic these roles should be able to find ways to work together taking into consideration the experiences of its members. In the previous case it could mean to create informal spaces that are also functional to the group objectives such as community fundraisers.

Another interesting prism to look into group culture is to regard groups as the site of interaction between a mainstream and its margins. In any group there are some characteristics or qualities that are favoured (mainstream) and others that are marginalized (margins). This dynamic is part of any group’s life and accepting this as the basis on which a group exist is fundamental: without the mainstream the group would not have a common ground, but without the margins a group would not grow.

The interaction between mainstream and margins reveals the ways in which we deal with difference. A group that gives space for sharing emotions, as well as giving and receiving feedback beyond frames of guilt and blame will be able to support its members to make choices about how do they participate and want to participate in the group.

Related to that matter, we need to acknowledge the strong emotional component that conflict involves. Emotional literacy gives us tools to better understand our emotional landscape, which is in turn, very connected to our capacity to express our needs from a place of connection with ourselves and our surroundings. That it is in my opinion key to come up with creative strategies to transform conflict into other ways of being together, and not to just passively mirror the needs of others or even the “needs” of a system where value has nothing to do with human and more-than-human needs.

Conflict transformation, at its core, means creating spaces for our emotions to transform. Spaces where we can recognize our needs and put them in a group context so that we can find together strategies and ways to mediate conflicting needs, as exhausting as it might be. Tapping into our inner landscape and those of others is a very vulnerable exercise and it can be at some times even confusing, when our understandings of feelings, needs and strategies are mixed with one another. For example if I say “I feel misunderstood”, I am not expressing a feeling but rather the veiled accusation that you are not understanding me. A question that could help me dig deeper into my emotional landscape would be “How do I feel when I feel misunderstood?”.

A key takeaway for me: standing in the contradiction of our experience is necessary to access the transformative power of working through discomfort. Jumping too quickly into conflict-resolution strategies, without space to fully share or disagree, risks leaving everyone dissatisfied. Conflict is very connected to discomfort and unease but those are just the symptoms of tensions that build naturally within groups.

It’s worth noting that emotional literacy, as framed here, is a concept that might not reflect how all communities experience or process emotion. In multicultural contexts, emotional expression often follows specific cultural codes, and communication between communities may be minimal or non-existent. Understanding the position of the person across from you is not just interpersonal—it’s political. It is about power, rank, and identity.

Beyond inclusion, beyond empowerment

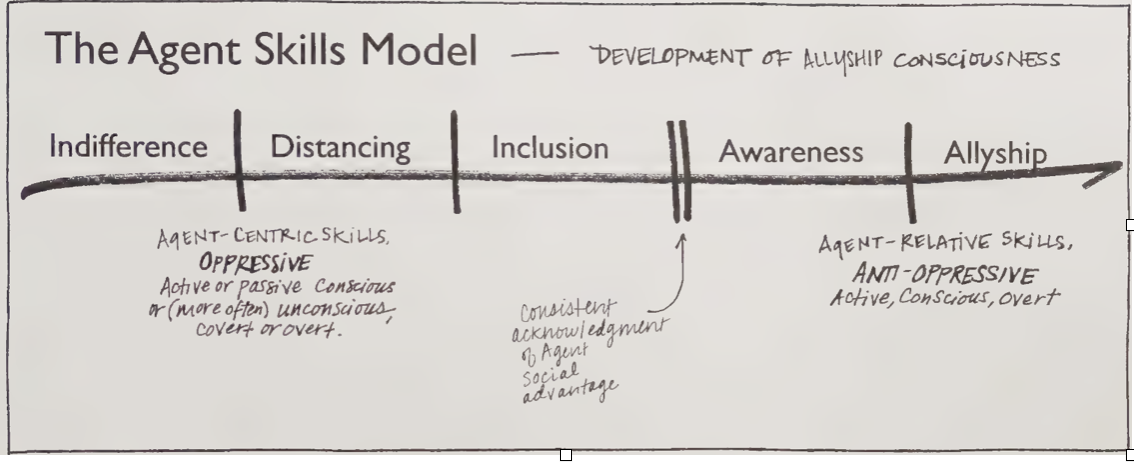

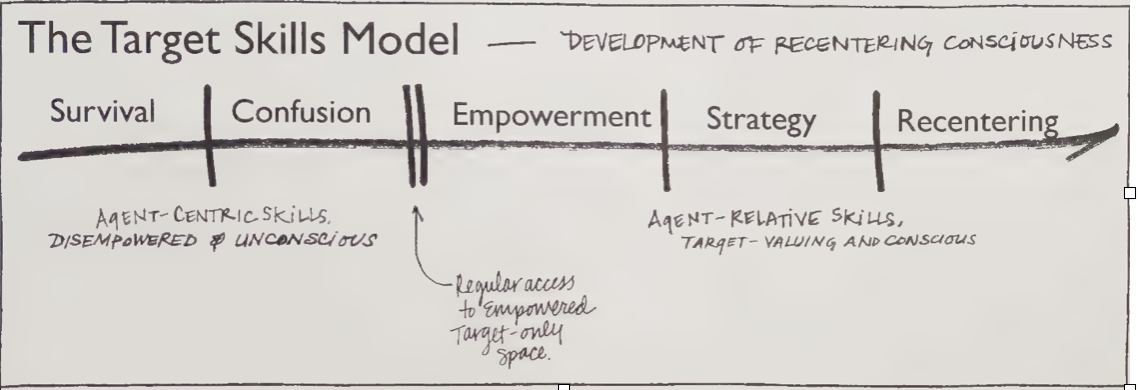

One powerful framework we explored was Leticia Nieto’s work, Beyond Inclusion, Beyond Empowerment. The basic argumentation of the book is that we live in societies where according to our multiple identities e.g. gender, ethnicity, disability, etc. we are given positions within society and assigned roles on how we must behave. Some parts of our identities can grant us privileges, while others can expose us to systemic oppression. Leticia Nieto argues that according to this we can differentiate between agent and target groups, meaning that agent groups would be those identities associated to having easier access to resources and being granted influence and dominance over other groups, while target groups are devalued just for being associated to a certain identity. According to Leticia Nieto, as agents and targets we develop some skillsets to navigate our social reality. In the case of agents connected to make ourselves and the people who share our agent rank comfortable, and in the case of targets to help us fit in with agent expectations for our group.

These skills aren’t linear or fixed—they’re coping strategies to navigate dehumanizing systems. The more of these skills we develop, the more we can face the discomfort of oppression with a sense of kinship and understanding, whether we’re agents or targets. This model resonated with me because it bridges the psychological and structural, allowing us to identify behaviours connected to the non-linearity of the human experience. It opens a path toward relating to others outside frames of blame and shame—and toward transforming conflict through shared humanity.

The conflicts that we inhabit

In the mist, there is clarity. Conflict is both a struggle and an art, and I’m only beginning to grasp its depth. As someone who prides himself on being diplomatic and socially engaged, it’s been hard to draw lines between the conflicts I carry inside and those that live around me. I believe they’re all connected—and that we must learn to live with the discomfort of a broken world without surrendering to its fractures. Mourning the loss of connection, while reopening bridges of communication, is part of the work.

A chain is only as strong as its weakest link. When working with communities, we must keep building containers and practices that can hold the complex, tangled realities of our shared lives.