This article is an outcome of the internship at Tesserae of Luigia Armillotta, Master Degree Student, University of Bologna, Master Degree course Politics, Administration, Organization- public policies and administration. It is the result of bibliographic research, urban exploration experiences, workshop participation, and interviews with entities engaged in diversity and inclusion in the area of Berlin. The aim of this article is to analyze how the concept of intersectionality can (and should) be applied within the city in its broadest sense. Starting from literature’s contributions concerning feminisms, intersectionality, and urban studies, the article will propose an analysis and identification of some good practices and potential role models implemented by actors operating in Berlin urban context in various fields, seeking to highlight the major challenges and critical issues.

With this set of tools, we will try to understand how necessary it is to adopt intersectional, more sustainable and inclusive models of urban planning and governance, in order to promote wider participation in city life by communities and all subjectivities who traverse and live in it.

The first two paragraphs will be devoted to the introduction of some key concepts, referring to the main literature contributions, and to the analysis of some contradictions and possible paradoxes concerning the topics discussed, through the help of some studies previously conducted. This in-depth preliminary analysis will provide a better understanding of the examples and contributions discussed in the third paragraph, as well as help to stimulate (and continue) the reflection proposed in the fourth and final paragraph.

CONTENTS

- A starting point: intersectionality and matrix of domination

- Safe space and communities : some potential paradoxes (segregation, internaldiscrimination, alienation)

- 2.1. A cue to overcome potential imposed (auto)segregation

- 2.2. The alienation and commodification of spaces and struggles

- 2.3. Building communities, beyond integration

- Some examples of good practices and models in Berlin

- 3.1. Starting from a deconstructed approach: the experience of CitizensLab

- 3.2. The emblematic example of public parks: how a good management can make the difference

- 3.3. Urban exploration as a learning practice: the decolonial tours

- The necessity of multidisciplinary approaches and methods: toward an alternative approach

1. A starting point: intersectionality and matrix of domination

Primarily, it is necessary to adopt a broader vision of “city”: a city to imagine not only as construction, physical space, but as a body of multiple subjectivities, in constant change, in a process of continuous negotiation between groups and individuals, characterized by power dynamics that are reflected in the relationships between groups. In this regard, we can refer to Paba’s (2010) contribution, for which the city is made out of thousands of bodies in their diversity and richness of genders, ages, lifestyles and consumption, sexual dispositions, religion and spirituality, geographical and cultural origin, physical and mental health condition, income levels or social position. In fact, the city is constantly negotiating with otherness. Therefore, this process is not something individual, but rather a collective exchange: it’s from the interaction of multiple individuals and subjectivities that this process takes place, both in a conflictual and a peaceful way, leading to the creation of communities and solidarity networks which may also be in contrast.

Connected to this is the second starting point: the city is not free from gender dynamics. Paraphrasing Kern (2020), the city is a “men’s city” built by those who did not take gender differences into account, so women’s daily experience and, broadening the vision and adopting a more intersectional lens, of those who do not belong to the category of able-bodied white hetero-cis men, is structurally conditioned by this. Power and domination are exercised mainly over certain categories of people, such as women, migrants, LGBTQIA+ communities (the acronym FLINTAQ*1 will be used throughout this article), disabled people, more generally all that is not embodied by the figure of the upper-middle class, able-bodied, white hetero-cis man. In light of this, it is necessary to draw on Crenshaw (1989)2 and Collins (2019) vision regarding intersectionality3: the differences of race, gender and class overlap and combine, determining interdependent systems of discrimination or privilege. To better understand how different forms of exclusion, power, and violence are constantly and more or less explicitly exercised on certain groups, we consider the “matrix of domination” theorized by Collins4: this is expressed in all its forms, affecting the experience and more generally the life of the most fragile and marginalized subjectivities within the city, in terms of crossing spaces, participating in decision-making processes and community life.

Self-representation and public recognition deeply influence the experience of the city, its space, and affect its access. The awareness of our positionality allows us to identify power relations: it can let us identify disparities and shed light on questions of design, accessibility, and quality of spaces and services with the objective of securing healthy lives and safe living conditions for everybody.

In the context of the right to the city, it is increasingly urgent to address challenges from an intersectional perspective, addressing the criticalities and violence that affect FLINTAQ*, migrants, disabled people by thinking of solutions with a multidisciplinary approach that has a comprehensive and intersectional vision.

2. Safe space and communities: some potential paradoxes (segregation, internal discrimination, alienation)

Fostering the construction and enjoyment of spaces and experiences that are safe, accessible and inclusive for marginalized and discriminated groups (mentioned above) is certainly one of the main issues to be addressed. However, a critical examination of this issue is essential, as the mechanisms of association, protection, and mutualism within the community of reference, while fostering a sense of safety and individuality, may inadvertently lead to ghettoization. In striving to create safe spaces where they can thrive and coexist, these groups risk isolating themselves from broader societal dynamics. This self-imposed separation may lead to exclusion and marginalization, as their efforts to self-organize against pervasive violence and discrimination could paradoxically confine them within their own circles. Consequently, they might find themselves both internally closed off and externally excluded, unable to engage in the wider processes necessary for their recognition and inclusion. Over time, this could render them invisible or limit their presence to their immediate community, further reinforcing their marginalization.

2.1 A cue to overcome potential imposed (auto)segregation

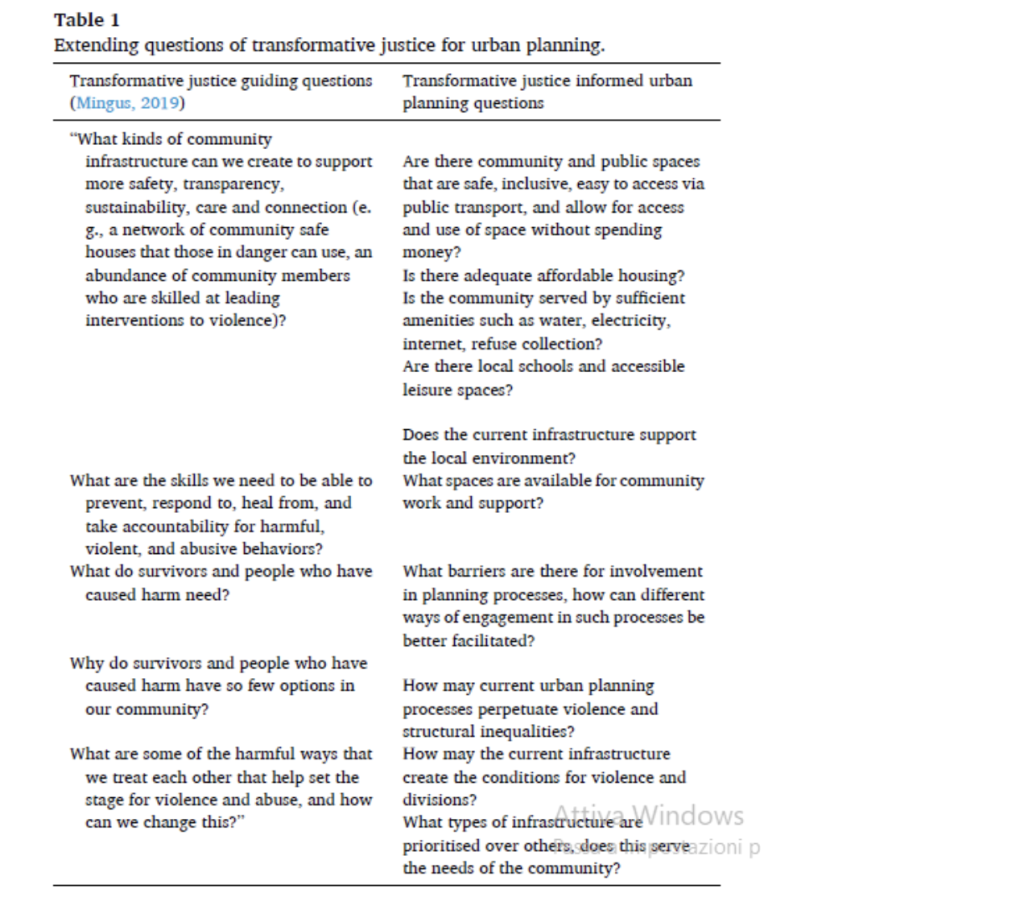

In this regard, it may be useful to draw on the concepts of “spatial intersectionality” and “transformative justice”, frameworks discussed in Forde’s (2024) study of “divided and post-conflict cities,” where more than elsewhere there is a need to adopt such paradigms in urban planning. In the context of this exploratory article, the focus on divided and post-conflict cities is not of primary interest to us, although Berlin history is marked by such experiences. Here we are interested in drawing on paradigms of spatial intersectionality and transformative justice to see how they can be a resource in the construction of the intersectional city, as frameworks that enable the implementation of urban planning capable of addressing the inequalities and divisions present in the city: “The application of spatial intersectionality and transformative justice in urban planning offers a framework to extend the work and approach of radical and insurgent planning and conceptualisations of the ‘just city’ with a necessary focus on the intersections of oppression. […] Spatial intersectionality can be used to identify how overlapping social categorisations such as racialisation, gender, disability, sexual orientation, age, class, and ‘colour’ interact with, are impacted by spatial planning and influence access to geographical spaces or resources” (Forde, 2024). In this regard it is useful and interesting the list of question proposed by Forde concerning transformative justice for urban planning:

A further insight provided by Forde is that spatial intersectionality can evidence those barriers to participation in planning and urban activism. Furthermore, infrastructure and cultural heritage spaces should be preserved in order to make the city more “just” and “equitable”. These two frameworks could boost a wider debate about an alternative place making process that addresses violence and divisions. By doing so, these complementary frameworks “have the potential to broaden the scope of urban planning to address inequity, violence, and division, and can support alternative modes of engagement with planning and reconstruction” (Forde, 2024).

2.2 The alienation and commodification of spaces and struggles

Returning to the question of potential segregation between and within the groups that make up FLINTAQ* etc. subjectivities, it is very useful and interesting to try to grasp the limits and broaden the perspective in an intersectional key. It’s useful to focus on an example: with respect to the queer community itself, we can see how it, over time, has been legitimized to proudly cross the city and claim its own spaces, but sometimes reproducing those same mechanisms of discrimination previously suffered, toward some components of the community. Indeed, one aspect that often escapes is how even within the queer community itself some groups are more legitimized than others and how they act out dynamics of power and overpowering others, replicating the pattern of discrimination and privilege already mentioned. Starting with the metaphor used by Crenshaw5 and making an ampliative effort, we can try to capture these dynamics. One of the most classic examples involves white gay men from upper-middle class backgrounds: these are the first to be legitimized and accepted. The same mechanism applies for nonwhite and noncisgender members of the queer community, whereby the process of acceptance, inclusion and the right to exist is often subordinated, as Crenshaw suggested as early as 1989, to the rights of the whiter, more cisgender, more able-bodied, more affluent slice of the community. Through such references and from this perspective, we can see how glaringly even within the same discriminated communities those same patterns of power and privilege are reproduced.

A further example illustrating the need and urgency of an intersectional approach is offered by Coffin’s et al. study (2017)6, which highlights the limitations of a single-issue approach and sheds light to the process of alienation of certain places, experienced as spaces of commodity and exchange, at the expense of a sense of community belonging and resistance. This research delves into how LGBT consumers perceive their local districts in relation to the broader urban landscape. It contrasts two perspectives: the notion of gay villages and the more prevalent gay ghettos, exploring the implications of these interpretations on LGBT identities and experiences within cities. The authors discuss the representation of Manchester’s Gay Village in media and its perceived diminishing role due to the city’s overall acceptance of LGBT individuals. Despite this acceptance, various LGBT social groups and events continue to thrive, suggesting a complex narrative that cannot be easily categorized.

The interviews conducted by the authors, aimed at exploring these narratives and the experiences of LGBTQIA+ residents, revealed that participants often viewed the Gay Village as a site of consumption rather than a community space: this is particularly significant since it highlights how certain struggles carried out by discriminated groups end up being commercialized (rainbow-washing), and this is seen and interpreted as a total acceptance of the community, now made so visible, rather than for the true commercialization that it is (think of the evolution of “gay pride”).

Furthermore, the authors suggest that future research should consider the semiotic relationships between places and include a more diverse sample of participants, particularly transgender and bisexual individuals. This conclusion testifies, once again, how intersectionality is often overlooked and how only the most acceptable component of that community according to societal standards is seen.

2.3 Building communities, beyond integration

In regard to what was introduced at the beginning of this paragraph, we can attempt to analyze community relations and the broader integration of certain FLINTAQ* groups, starting from the study conducted by Brown-Saracino “From the Lesbian Ghetto to Ambient Community: The Perceived Costs and Benefits of Integration for Community” (2011), which introduces and theorizes the concept of ambient communities (it can be summarized as the social bonds that form not necessarily through shared sexual identity, but rather through common interests and activities). From this, we can grasp the most innovative aspects as well as some potential limitations of what Brown-Saracino has theorized.

The study explores the dynamics of lesbian communities and the transition from a ghettoized community to a more integrated and ambient community. Therefore Brown-Saracino’s study offers a new perspective on the dynamics of lesbian communities, emphasizing the importance of integration and relationships based on shared interests rather than exclusive sexual identity. The objective is to analyze how lesbian women perceive the costs and benefits of integration into broader communities, compared to life in ghettoized spaces, and how these experiences influence their social relationships and sense of community. The study highlights that, although racial and class identities are present, they are not always considered fundamental characteristics for building bonds, unlike in ghettoized contexts.

However, it is important to point out that this study presents some limitations and gaps concerning the intersectional approach, such as the circumscribed territory of inquiry and the general profile of the interviewees7. The emphasis on integration and ambient community may overlook the ongoing challenges and barriers faced by marginalized groups. While the study highlights positive aspects of integration, it may not fully address the complexities and struggles that persist within these communities.

In light of Brown-Saracino’s study, whether on one side it’s possible to appreciate the effort to create more fully integrated communities, transcending the specific characteristics of certain groups (which, it should be noted, must be protected due to past and present discrimination), and draw on this concept to foster more complex bonds by overcoming certain ghettoization, the result remains partial and limited from an intersectional perspective. As mentioned above, the sample of interviewees and the context of reference are not indicative of the more complex reality in which FLINTAQ* communities daily live. Therefore, overcoming the vision of communities with a strong identity could sometimes be premature and dangerous if not appropriately calibrated through a deeply intersectional approach and reflection.

3. Some examples of good practices and models in Berlin

Through urban exploration, workshops participation, and interviews, it was possible to collect several relevant experiences and testimonies from organizations working in the fields of diversity and inclusion. These findings offer a perspective, albeit partial, on potential best practices and models for imagining and bringing to life an intersectional city. Specifically, attention will be given to the management of public parks through the contributions of FeministPark collective and Think SI3, examining interactions among various actors and recognizing the real issues highlighted above. Regarding community relations and the deconstruction of certain individualistic relational models for a regenerative culture, the testimony of CitizensLab will be referenced. Additional references will be made to associations and activism groups.

The contribution offered in this exploratory article is partial, but it can serve as a good starting point to identify possible pathways and begin to map those (non)-places in the city of Berlin for the construction of an intersectional city.

3.1 Starting from a deconstructed approach: the experience of CitizensLab8

CitizensLab (CL) is a European network of local actors/practitioners of change. Born in 2016, this network has been experimenting, prototyping and inventing with citizens new forms of expression, shared narratives,commonalities, shared spaces, real or symbolic. Since November 2020 CitizensLab has become a registered NGO in Berlin, aiming at working locally as well as internationally.

CL starts in 2016 as a pilot project within a German organization: basically it was an experiment to see how different actors of social transformation and change, operating in several sectors from being involved in NGOs, activism, self-organized communities, artists, practitioners, as well as policy makers and people working in public institutions acrossEurope could gather and network to share practices, solutions, models concerning local issues and challenges and to connect globally, as a multidisciplinary network.

However, after three years, the fundings ended but a core team of the existing European network decided to continue with CitizensLab as a living lab and self-organized entity. The caring team developed a new theory of change and vision for the CitizensLab, aiming for an inner-to-outer intersectional transformation process within societal change — a significant shift occurred. They began to develop and design experiential learning formats, workshops, and gatherings. Within CitizensLab they bring a regenerative approach into the field of social justice, societal transformation and citizen engagement, integrating the cognitive, the emotional and the physical body as they seek to rewrite current narratives of democracy.

The final phase is now focused on becoming more locally based and structured in Berlin (while until now meetings and workshops were online or across Europe in spaces where members were active).

After all these experimentations and experiences, and thanks to a collaboration with ULEX, a learning center in Spain, CitizensLab came to be a community of practice. Rather than a physical space, they’re a platform where they share practices and knowledge. Contributions come from members of various collectives and communities, fostering a collaborative environment. One of their main resources is the shared open-source materials available on their website.

Vision, mission and goals

Starting from the ideas that we need a radical shift in the society we’re living within, and the way we relate both to each other and to ourselves is a core issue, the change we need can only happen if based on renewed caring relationships and kinship, based on a regenerative culture. CL questions about how to nourish competencies related to care and commoning, by proposing four core pillars for regenerative culture:

● Care and Kinship – Extending the definition of family and care to encompass all relations, acknowledging that our well-being is deeply interwoven with the well-being of others.

● Living Systems Worldviews – Embracing the complexity and interdependence of life, recognizing that our actions ripple through the web of existence and overcoming the dualism of the separation such as, body-mind, human-nature.

● Power Dynamics – Engaging with power not as a tool of oppression but as a potential force for equity and justice. (Un)learning and recognizing how power is framed, our privileges and the forms of power we have internalized and the ways we reproduce and live them. Learn to deconstruct and use privileges to build stronger movements of intersectional alliances and collective power.

● Decolonial Thinking – Committing to unravel the tightly wound threads of colonial impact on our minds and societies, which comes from imperialism, and capitalism of white supremacy, as well as patriarchy to craft spaces for multiple truths and forms of wisdoms.

We need to be open to learn and unlearn collectively, in order to overcome the limits of the society we live within and create a regenerative culture, as a tool to face conflicts in atransformative way: “Intersectionality starts at the interrelation with each other” (CitizensLab’s team).

Activities and targets

CLab registers a really wide range of participants responding to their calls for applications, 20-40 people for each call and workshop they’ve been organizing. CLab activities are organized around the current action-research inquiry around competences to create, host and nourish Cultures of Care, Commoning and Kinship to radically imagine new forms of democracy, collective organizing and a more just society.

CLab activities include workshops on “Participatory Leadership” based on the the Art of Hosting and Harvesting Meaningful conversations focused on holding space for societal transformation and facilitation practices. CLab formats also include experiential in-person or online “Learning Journeys” to explore and deepen the learnings around the four pillars for Regenerative cultures.

In Berlin, CLab is focusing its activities in hosting a “Regenerative Cultures for Societal Transformation Community of Practice (CoP)” that is aiming at creating peer-learning exchange among people (facilitators, activists, artists, change-makers, social innovators, …) dedicated to bring regenerative approaches in social transformation processes. The concept of regenerative cultures implies to center how we relate to the land, to one-another, and to our bodies. This relational approach is core to how we practice our respons-ability, how we activate our collective agency and power, our creativity and radical imaginations to build just, resilient communties. Another community space, activated by the emerging initiative Collective Care Berlin, is the series of free monthly workshops “ A call to Regenerate”, which is aiming at supporting the Palestinian liberation movement in Berlin.

The general intent is to create (also) solidarity networks.

Interactions and difficulties

CL has strong collaboration also with other active organizations in Berlin, especially with Oyoun, a cultural center defined as a queer decolonial space. However, due to the repressive climate in the city (especially due to pro-palestinian movement) lot of difficulties and limitations concerning fundings came out (Oyoun’s funds have been cut for several months).

Regarding the difficulties and main challenges that CitizensLab’s team typically face, they note that a significant issue is that much of the work remains unpaid due to insufficient funding. This highlights the fact that these initiatives and organizations are not regarded as legitimate work and do not receive sufficient attention in terms of funding and recognition of their societal role. As a result, all types of “care work” are marginalized.

They also say they apply for various funds (public, european, private), but these are often designated for specific, single-issue projects. As a result, the CLab team frequently needs to adapt and modify their proposals, sometimes accepting minor compromises. However, it is very challenging to secure funding since their approach is more intersectional rather than focused on a single sector. Consequently, they often end up with limited or no resources.

Additionally, they face strong competition, particularly from organizations working with migrants. These challenges testify the lack of recognition and acknowledgment of the issues faced by CitizensLab, revealing a persistent sectorial and non-intersectional vision among funding bodies. The operators also reported difficulties in being accepted or considered if they held more radical positions on certain issues, noting a pro status-quo approach from the funding organizations.

The operators assert that there is still no funding mechanism that supports a multiple approach, forcing organizations to make compromises that ultimately prove ineffective.

The change we need must also address these funding mechanisms and strategies, especially in the social work sector, as the current system is rife with criticalities and contradictions.

3.2 The emblematic example of public parks: how a good management can make the difference

Public parks can be emblematic spaces for a dual reason: on one hand, they reflect mechanisms of exclusion, perceptions of safety, and accessibility, often marginalizing FLINTAQ*, migrants, disabled individuals and being socio-culturally confined to certain groups within the city. On the other hand, precisely because of these issues, parks can serve as a starting point for renewing and revolutionizing urban green space planning from an intersectional and feminist perspective.

In order to better understand this kind of issue, here’s the example of Tempelhofer Feld: since it was converted into an urban public space, there has been a noticeable predominance of white individuals compared to the more ethnically diverse population of the city. To address this, a study and interviews were conducted to understand why non-white people were not frequenting the park. This led to the idea of creating more inclusive areas and dedicating certain park spaces to specific activities, making the environment more welcoming for various target groups, such as families. This approach contrasted sharply with the initial, erroneous conclusion that the park simply did not interest non-white communities. It highlights how certain spaces, if not properly managed, designed, and structured—whether through urban planning, participatory policy mechanisms, or other means—can become sites of segregation and exclusion for some societal groups.

A significant network that has recently begun exploring this topic and gathering best practices is The Feminist Park collective (TFPC)9: this project endeavors to rewrite the mainstream narrative, infusing these green urban spaces with the richness of diverse voices and experiences. TFPC aspires to create environments where everyone can feel seen, safe, and valued.

To advance its mission, the Feminist Park Project hosts a variety of events that foster dialogue and engagement. One of the last one took place on the 6th of July 2024, gathering people coming from different backgrounds, as well as some workers and experts in the field, where one of the main contributions was that of a project manager of Think SI3 who presented park management strategies and formats.

These activities collectively contribute to the project’s objectives by promoting intersectional eco-feminism, environmental justice, and the creation of anti-racist green urban spaces.

Park management and inclusive formats from Think SI3

Think SI3 (TSI3)10 is a dynamic company specializing in developing new approaches to preventing and ensuring safety in public spaces. Their goal is to make the urban environment safer and more liveable, thus contributing to social cohesion.

Think SI3 was founded in 2019 and initially focused solely on park management, collaborating closely with SI3 (the sister-company that provides the Parkläufer and other workers for other projects.). The team primarily consists of park coordinators who handle interactions and communication with people in streets and parks, including conducting surveys. Additionally, TSI3 undertakes independent projects related to urban analysis, with a particular emphasis on perception of safety in public parks and green spaces. They are also involved in projects addressing nighttime lighting in various neighborhoods, including Regenbogen Kiez—a well-known queer area. These projects aim to mitigate potential intercultural conflicts and reduce the risk of violence against communities, such as the queer community. TSI3’s role centers on facilitation, mediation, and raising awareness to prevent conflicts and acts of violence.

Their main tools are based on the collected data through the surveys and questionnaires the team submit to citizens.

Since TSI3 approach is to combine safety with social aspects, in order to implement some more sustainable and alternative solutions, they don’t target specific groups, rather they submit surveys to people in general, trying to analyze and balancing interests: they operate at the basic level, where the interaction with people is horizontal, as a peer-to-peer exchange. By doing so, TSI3 team tries to identify and analyze the needs and criticalities which occur among different social groups, and act as a mediator between them, when there are some conflicts or prejudices. The winning approach is the fact that the team doesn’t act from a top-down approach (like, they suggest, in the case of police-sex workers; homeless people-police, etc.), rather they search for a dialogue and equal interaction, building trust bonds with the people they interact with.

Of course, they also register some difficulties in balancing interests and finding compromises according to the needs which emerge from the interviews, since every social group and individual has different needs and vision of the city they want. In this context, TSI3 contribution may be defined as preventing conflicts, acting as mediator, in a really complex process where human interactions and people’s needs are at the core of their strategy.

In this way, the TSI3 team acts as an advisor and consultant, able to register and report the community’s actual needs to the local government based on collected data and actions on the field. Their role is also intersectional, as they mediate among various social groups and engage with multiple levels of government and society—from citizens to local authorities—while cooperating and collaborating with other local organizations.

Some good practices

The main project format is of „Parkbetreuung“, where TSI3 provides Parkmanagement and Parkläufer, while Awareness Team is one of the newest formats11, active since 2023 in Schlachtensee and since 2024 in Mauerpark. This format12 is an example of care of the space but also toward those who use and cross it, particularly relevant for often marginalized groups such as migrants and undocumented individuals who typically rely on marginal and illegal segments of the market. Consider also homeless individuals and FLINTAQ*, who are at high risk of harassment and often forced to avoid places like parks due to safety concerns.

We can analyze some examples which highlight their peer-to-peer and intersectional approach to public issues through social lens. Here are some experiences they told.

Sex workers: this is an emblematic category, since they never call the police or/and claim for help from nearby residents, since, as the TSI3 operators state, the latter don’t like or even hate them, because of sex workers stigmatization. In this context TSI3 team is the one of the actors who can play a mediation role and help them, contributing to deconstruct the negative and stigmatized idea of these people. In this sense TSI3 de-escalate conflicts.

Playground in Schoeneberg neighborhood close to a car-free street: teenagers gathered in that area and that bothered the owner of the building, who was complaining and threatened to report and kick-out the youth center which was nearby (he blamed the youth center for being the attraction point for teenagers). In this context, TSI3 mediates and uses a peer-to-peer approach: at the beginning the team documented the situation and collected some evidence. After this initial phase, team members talked to the guys, registering a really collaborative attitude from them, in order to make them understand the situation: thay simply asked them to adapt and make some little changes in their behavior, so both parties could enjoy the area. In this sense TSI3 acted as an intersectional-intergenerational mediator, using an alternative communication and approach to solve social conflicts.

Playground in Kleistpark: there was a conflict between two main groups of children- one of german and english speakers kids and the other of arabic speaking ones, where the latter had a rather aggressive attitude. The TSI3 team’s action was to mediate through the practice of play: every day in the afternoon, the two groups were to play together with the Parkläuferin order to establish a contact with both groups and encourage a fair interaction between the groups and it worked: as soon as there were some problems, they called them or came to their info-point. This approach had a dual function: it was both mediative and educational. It aimed at fostering inclusion and promoting the sharing of spaces.

Drug dealing in Goerlitzer Park13 – inside the park, there have been tense situations and conflicts due to groups of migrants dealing drugs, even during times when the space was frequented by families and children. The invasive and repressive police actions proved ineffective. The TSI3 team’s action is innovative because it is based on a more horizontal and dialogue-driven approach. The founder, who is also a Parkläufer himself in Goerlitzer Park, used his linguistic and personal skills to seek contact and establish a more trusting bond with those involved, achieving positive results.

Police vs peer-to-peer approach: a little digression about TSI3 approach

A particularly interesting aspect that emerges from the examples analyzed is the minimal contact with law enforcement, limited to only what is strictly necessary. Law enforcement is often perceived as a threat rather than as help and protection. The team strives to work as independently as possible, contacting the police only in emergencies. By operating in this manner, there is a greater opportunity to establish a bond of trust and relationship, laying the groundwork for increased awareness of the space and how it can be navigated and experienced. This approach also aims to educate, but informally, through relationships and interactions.

In this regard we can relate this issue to the study carried out by Angeles and Roberton (2018)14, Empathy and inclusive public safety in the city: Examining LGBTQ2+ voices and experiences of intersectional discrimination- which focuses on on discrimination in urban spaces, analyzing how personal characteristics may influence the perception, as well as the interaction with other people, especially with white-male ones and police, with regard to LGBT+ community. An interesting point of view offered from this study is the attention put on the emotional side, that is the empathy and trust to institutions such as the police, or more in general the public side. Moreover, a deeper approach is given by the analysis of the interactions among the LGBT+ community members concerning the reporting to the police and, more in general, coping mechanisms caused by violence, aggression and discrimination. Through the reporting work collected in the case study of the city of Toronto, interesting critical aspects are highlighted and may constitute a good start for a more general reasoning about the topic, in order to wide and spread the perspective and try to investigate the same in other context (for example through some urban exercises).

Interactions and difficulties

TSI3 is a private company, but works for and with public projects, applying for public funds: they take part in public competitions with security companies, which, they state, is quite often a problem, because almost everything depends on how the public call is structured, TS3 team assert that often it focuses rather on the costs, rather on the social aspects of work of a company. So sometimes companies, which have a pure security-approach , win the competition. Furthermore, it’s something that lasts for a couple of years and then the company cannot count on something regularly: the company does not have a secure future and that the work is really seasonal, which makes it lose some workers and the knowledge and social contacts which they have.

Regarding interactions with local institutions, the experience varies significantly, as it depends on the internal situation of each administration. The main difficulties are typically related to bureaucratic delays in receiving responses and authorizations to proceed with projects, but this aspect is also highly variable. These delays often lead to setbacks in urban analyses, which in turn affect the implementation of projects. For example, one operator reported waiting eight months to get approval for a questionnaire on park safety perceptions. Moreover, their autonomy also depends on how each district’s administration allocates money and addresses fundings and which are the fixed priorities they want to focus on.

It should be noted that much depends on the political situation, which affects these aspects as well. Project managers observe that in areas with a significant presence of certain political actors, there is less likelihood of interaction and approval for initiatives like those proposed by TSI3.

Regarding collaboration and cooperation with other local organizations, they strive to establish communication and partnerships. They aim to connect migrants with the local population by implementing workshops and socio-cultural activities.

Learning from TSI3

To sum up, TSI3 aims to bring together diverse interests while finding a balance, always focusing on a sense of safety, which means more than just ensuring the absence of harassment. They strive to find alternative and peer-to-peer solutions. Moreover, their intersectional approach is evident in the percentage of non-German-speaking migrants working within the organization, encouraging a learning-by-doing method that is very open and inclusive (the founder he’s a migrant, from Guinea). Regarding women, they are working towards greater participation despite the dangers of traversing certain areas. They are attempting to deconstruct these barriers and create a safe space and method of work and interaction.

In light of this reflection and example, it becomes even clearer how necessary it is to design and build spaces that consider the challenges faced by more vulnerable and marginalized groups. It is also crucial that this is accompanied by an administrative process that supports such initiatives to develop a well-structured and ingrained approach to prevention, inclusion, and care. The example of ThinkSI3 serves as a good practice,providing a boost for envisioning more sustainable and structural policy solutions. This can mark the beginning of a paradigm shift regarding the urban environment, seen both as a space and as a community of people who use it.

Moreover, fostering interaction and potential peaceful collaboration between organizations like TSI3 and law enforcement could be a good practice in redefining the concept and perception of safety and public order, especially given the often more restrictive and punitive approaches used by the police.

3.3 Urban exploration as a learning practice: the decolonial tours

Another interesting and powerful tool we can use to recognize and deconstruct urban spaces, and the socio-cultural vision we have about that, is city exploration tours together with urban reconnaissance exercises.

In this regard Dekolonial Tours (DT), in Berlin, offers different options of guided tours, focused on different topics related to intersectionality, such as Black and Queer Feminism, African continent history, colonialism and how it’s intertwined with Germany and in particular with Berlin historical sites.

The idea of Dekolonial Tours teams is that through an informed and aware vision about what happened in the past, we can use such knowledge to face and dismantle racism and the system of oppression and domination which is still alive and present, due to centuries of colonialism. During colonialism, many explicitly racist structures and systems were introduced, the consequences of which can still be felt today and have a lasting impact on many areas of life, such as culture, politics and the economy. By shedding light on this history, DT team aims at helping to bring about even more lasting change.

“With our guided tours, we want to break the taboo of talking and discussing colonialism and its lasting effects. In this way, we can encourage conversation and create a solution-oriented mindset when it comes to creating a new and more just world.”

DT strategy is based on 3 pillars:

– equal rights: in order to give to everyone the opportunity of self-determination, only achievable through a deep process of decolonization, by questioning and changing power relations. The aim is to enable equal participation of all people in society.Decolonial tours may be a powerful tool of learning practice, which enable to better understand and see urban spaces and the relations and interactions that occur in it, in order

– recognition: in order to understand and recognize the affection and involvement of everybody in colonialism, a critical examination of the past and a reassessment of historical events is necessary;

– unlearning racism: in order to overcome racist structures and discrimination, which is a central aspect of decolonization; to make people and policy makers more aware of certain issues, so they can shape and plan more just and equitable policies.

4. The necessity of multidisciplinary approaches and methods

“Substantively, communities that incorporate people who theorize from the bottom up as well as from the top down can produce a wealth of new questions, interpretations, and knowledge that is far more concerned with changing the existing social order than in explaining it. Methodologically, this dialogical way of producing knowledge elevates the significance of intellectual and political coalitions and alliances within interpretive communities above the brilliance of the individual intellectual.”

Patricia Hill Collins (2021)15

Starting from Collins’ words and in light of what has emerged through this research, it is clear that a multidisciplinary approach and the involvement of various actors are necessary for the construction of an intersectional city in all its meanings and facets (urban space planning, socio-cultural vision of communities and deep inclusion of all groups that compose society, participation and representation, etc.).

It is essential that representatives of public institutions, private entities, civil society, and the academic research world collaborate closely, in order to address the complex dynamics of exclusion and discrimination marginalized communities experience. Multidisciplinary approaches allow the integration of different perspectives and expertise, ensuring more holistic and inclusive solutions.

Public institutions can provide the regulatory framework and necessary resources. Addressing certain issues, and more generally, paying attention to them and incorporating them into the political agenda, confer legitimacy and credibility to these demands, allowing them to go beyond activism and associationism. These are almost always confined to certain realities, which are often hindered and repressed by the same public institutions.

Private entities operating in various fields can contribute with technological innovations and funding, such as companies involved in architecture and urbanism or those working in the field of social innovation. Their role in advocacy and consulting is fundamental and certainly not marginal in this context.

Civil society, that is associations, activist groups, and advocacy groups, can offer valuable insights into the real needs of communities. There are numerous examples of this, although they often concern only a small part of the citizens, mostly the more sensitive component to or personally affected by certain issues. It is also important to emphasize that citizens’ participation and social activism alone cannot replace concrete action taken and led by the State. Although the examples of possible alternatives offered by this sector are diverse, they are often repressed by the State and its institutions. Instead, concerted action is necessary, involving civil society actors alongside other stakeholders.

Equally important is the contribution of the Academia, which can provide data, research, and critical analyses to inform and guide policies and practices. As analyzed throughout this exploration, studies can serve as starting points for reflection, highlighting limitations, best practices, and innovative processes that can help in the formulation and implementation of more effective policies and interventions.

Only through a synergic and intersectoral collaboration it will be possible to create urban spaces that truly reflect the diversity and complexity of human experiences, promoting equity and justice for all subjectivities.

One of the concrete methods to implement what has been discussed is participation and direct involvement. As Collins (2021) states, “Building participatory, democratic interpretive communities across differences of experience, expertise, and resources has been the hallmark of intersectional projects.”. Clearly, superficial participation is not enough for the radical and structured construction of an intersectional city. Before discussing the participation of these subjectivities, it is necessary to make them visible and give them greater dignity and the right to exist. Therefore, their involvement must be genuine and not superficial, following the addressing of certain issues by institutions and stopping the repression often faced by bottom-up alternatives.

The deconstruction of those systems of domination and discrimination through an approach based on care, solidarity and the recognition of otherness allows us to refill the city with new meanings, symbols and ways of being together. Building an inclusive and caring public space need a participatory approach which must involve different actors coming from several fields, such as local civil society, public institutions, private actors, research and development institutions (i.e. University): only through a horizontal and bottom-up analysis and creative process, it would be possible to shape the intersectional caring city.

Authors

Luigia Armillotta

References

Angeles L. A., Roberton J. (2018), Empathy and inclusive public safety in the city: Examining LGBTQ2+ voices and experiences of intersectional discrimination, Women Studies International Forum, University of British Columbia, Canada

Brown-Saracino, J., (2011), From the Lesbian Ghetto to Ambient Community: The Perceived Costs and Benefits of Integration for Community, Social Problems , Vol. 58, No. 3 (August 2011), pp. 361-388

Coffin, J., et al. (2017) ,Revisiting the Ghetto: How the Meanings of Gay Districts Are Shaped By the Meanings of the City, in NA – Advances in Consumer Research Volume 44.

Collins P. H. (2019), Intersectionality as social critical theory, Duke University Press, Durham and London

Collins, P.H., da Silva, E.C.G., Ergun, E. et al (2021). Intersectionality as Critical Social Theory. Contemp Polit Theory 20, 690–725 https://doi.org/10.1057/s41296-021-00490-0

Crenshaw, K. (1989) Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics, University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 1989: Iss. 1, Article 8.

Forde S. (2024), Spatial intersectionality and transformative justice as frameworks for equitable urban planning in divided and post-conflict cities, Cities journal n. 147, 104796

Huang K., Jin J., Zhu Mingyu (2023) Engendering the City: A Participatory Approach to Gender- Responsive Planning and Urban Design in Cairo, in Urban Poetics and Politics in Contemporary South Asia and the Middle East, chapter 13, pp. 269-290, IGI Global

DOI: 10.4018/978-1-6684-6650-6.ch013

Kern L. (2020), Feminist City: Claiming Space in a Man-Made World, Verso

NOTES

1 FLINTA* is a German abbreviation that stands for “Frauen, Lesben, Intergeschlechtliche, nichtbinäre, trans und agender Personen”, meaning women, lesbians, intersex, non-binary, trans and agender people. The asterisk represents all non-binary gender identities. To explicitly include queer individuals, the term FLINTAQ is sometimes used, expanding on the FLINTA acronym (source: wikipedia.org , consulted on 26/07/2024)

2 Crenshaw K., (1989), Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique o Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics, University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 1989: Iss. 1, Article 8. Available at:http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8

3 “The complexities of the multiple resistant knowledge projects that inform intersectionality lie in the parallel and intertwining narratives of Indigenous peoples, refugee and immigrant groups, women, LGBTQ teenagers, religious and ethnic minorities, and poor people. These and other similarly subordinated groups also find themselves facing social problems that can neither be understood, nor solved in isolation.” in Collins, H.P., (2019), Intersectionality as Critical Social Theory, Duke University Press.

4 Collins, P., H., (2000), Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment, Routledge. This matrix of domination is made up of the interaction and intersection of 4 domains: structural (organizing power and oppression), disciplinary (sustaining oppression), hegemonic (legitimizing oppression) and interpersonal (controlling the interactions and consciousness of individuals), ringing to different forms of oppression, concerning race, gender, socioeconomic status, ages, sexuality.

5 “Imagine a basement which contains all people who are disadvantaged on the basis of race, sex, class, sexual preference, age and/or physical ability. These people are stacked-feet standing on shoulders-with those on the bottom being disadvantaged by the full array of factors, up to the very top, where the heads of all those disadvantaged by a singular factor brush up against the ceiling. Their ceiling is actually the floor above which only those who are not disadvantaged in any way reside. In efforts to correct some aspects of domination, those above the ceiling admit from the basement only those who can say that “but for” the ceiling, they too would be in the upper room. A hatch is developed through which those placed immediately below can crawl. Yet this hatch is generally available only to those who-due to the singularity of their burden and their otherwise privileged position relative to those below-are in the position to crawl through. Those who are multiply-burdened are generally left below unless they can somehow pull themselves into the groups that are permitted to squeeze through the hatch. As this analogy translates for Black women, the problem is that they can receive protection only to the extent that their experiences are recognizably similar to those whose experiences tend to be reflected in antidiscrimination doctrine. If Black women cannot conclusively say that “but for” their race or “but for” their gender they would be treated differently, they are not invited to climb through the hatch but told to wait in the unprotected margin until they can be absorbed into the broader, protected categories of race and sex.” Crenshaw, K., (1989) “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique o Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics,” University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 1989: Iss. 1, Article 8., pp.151-152. Available at:http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8

6 Coffin, J., et al. (2017), Revisiting the Ghetto: How the Meanings of Gay Districts Are Shaped By the Meanings of the City, in NA – Advances in Consumer Research Volume 44

7 The study considered the specific social, cultural, and geographic context of Ithaca (New York), which is characterized by a high proportion of queer women and a relatively accepting environment. Furthermore, the relatively small sample of informants (only two biracial individuals, one Latina, and one Asian woman; the rest identify as Caucasian) limits the generalizability of the findings to other contexts or populations, especially in different geographic or cultural settings.

8 The information that follows is an elaboration of what emerged during the interview with two collaborators and project managers of CitizensLab. More information about the organization are available here: citizenslab.eu

9 For more information, consult: feministpark.com

10 more information about the organization and their projects are available at this page: think-sihoch3.com

11 Just to clarify: Parkmanager is responsible for the networking, data analysis, planning of urban interventions, developing the action strategy and training of the Parkläufer. Parkläufer are daily in the park/in the district and collect data, talk to people, de-escalate conflicts etc.

12 It is primarily addressed to party people.

13 In this regard, a clarification is necessary to stimulate broader reflection: why do these individuals choose (if it can be called a choice) to engage in illegal activities such as drug dealing? This is often linked to the lack of documents, like residence permits, which are necessary to find regular and legalized work. Therefore, it is crucial to address the root of the problem and recognize that this is a “fictitious” issue masking a deeper one rooted in racism and propaganda. Clearly, this matter extends far beyond urban space management and must be tackled through policies of inclusion and participation (in work and, more broadly, community life) for racialized individuals, involving social, migration, and welfare policies. When considering other marginalized groups, as mentioned, the need for such policy becomes even more evident. This can only be achieved if it is placed on the agenda and deemed worthy of attention by the political class.

14 Angeles L. A., Roberton J. (2018), Empathy and inclusive public safety in the city: Examining LGBTQ2+ voices and experiences of intersectional discrimination#, Women Studies International Forum, University of British Columbia, Canada

15 Collins, P. H., da Silva, E. C. G., Ergun, E., Furseth, I., Bond, K. D., & Martínez-Palacios, J.; (2021), Intersectionality as Critical Social Theory, Patricia Hill Collins, Duke University Press, 2019. Contemporary Political Theory, 20(3), 690–725. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41296-021-00490-0